Research

Internal state and habitat selection

Internal states - latent variables that define our motivativations - shape behaviour in many animals. For example, elevated cortisol is one of the hormonal signals for hunger during daily energy and activity cycles. Cortisol peaks also occur seasonally when female mammals must devote large amounts of energy to produce milk for their offspring. I am integrating measureable internal state variables into quantitative movement models to understand how internal states shape the space use of individual organisms. I found a relationship between cortisol production and preference for energy-rich agricultural cropland by female elk with newborn calves. Elk preferred cropland when their cortisol levels were elevated, and this relationship became stronger as their calves grew older. Read the publication here.

Quantitative tools for wildlife health

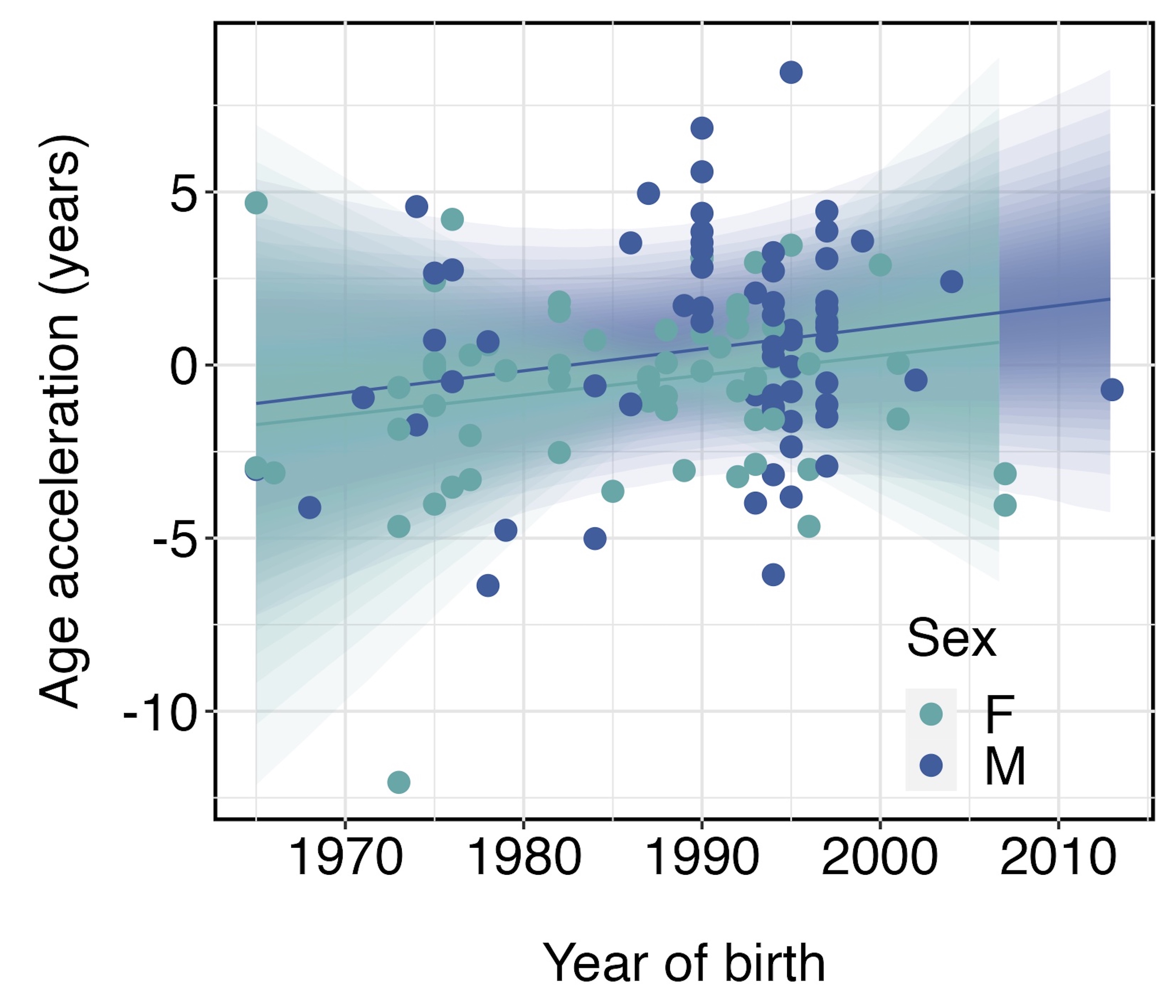

As most organisms age, epigenetic marks are gained and lost from our DNA at such predictable rates that measuring them can serve as a biological clock. Epigenetic clocks tick faster when we experience stress in our environments, making them a popular tool for understanding relationships between environmental stress and disease and time-to-death in humans for more than a decade. I design epigenetic clocks connecting environmental stress to internal states in wildlife. For example, polar bears near Churchill, Manitoba are declining because of decades of stress from climate change. Bears born more recently, who experienced more stress over their lifetimes from climate change, also aged faster epigenetically. Read the preprint here.

From individuals to global patterns

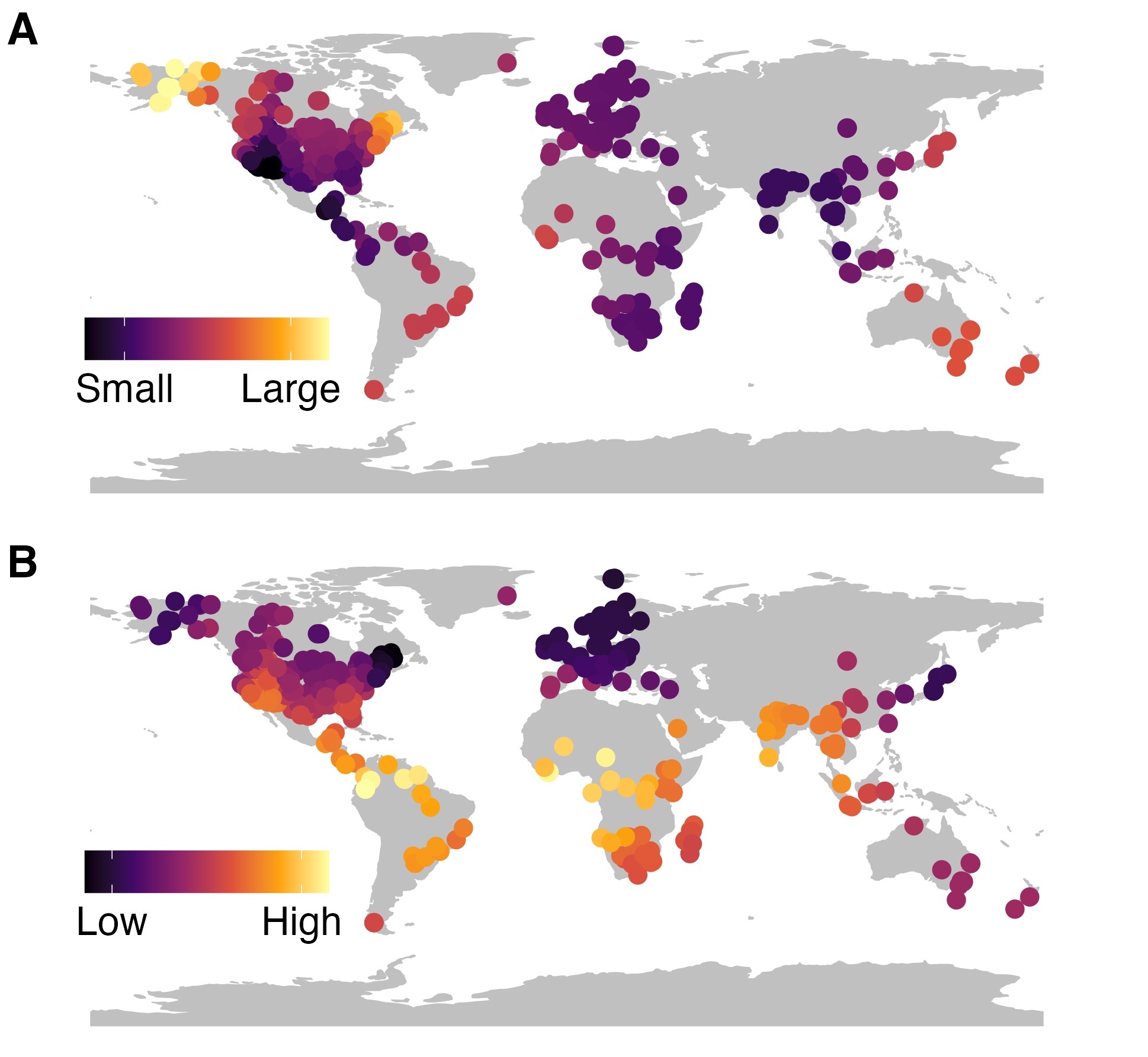

Questions about global biodiversity patterns have long puzzled ecologists. For example, why are there so many species at low latitudes and fewer at high latitudes? Why are species ranges larger at high altitudes? These and other questions have been investigated at local scales, but generalizing findings to global biodiversity patterns was difficult until recently when data from individual organisms became widely available at global scales. I synthesize data from individual organisms to test whether local-scale phenomenon scale up to global biodiversity patterns. For example, I am tested for a global relationship between mammal home range size and species richness, hypothesizing that where individual mammals use smaller ranges (panel A, right), species richness is higher (panel B, right) because more species can coexist.